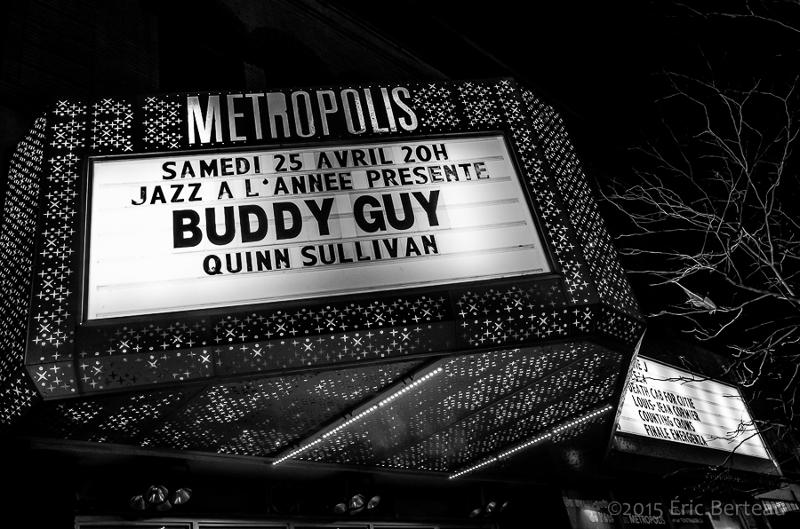

Buddy Guy and my guy

Photos: Eric Berteau, ericberteau.piwigo.com

I took my guy to see Buddy Guy at Montreal’s Metropolis on Saturday night, and now I can hear him in his room, playing blues licks on his leftie two-tone Strat. Last week he was practising “Old Pigweed,” a Mark Knopfler tune. This week his head is more into the blues, thanks to Buddy Guy.

And not just Buddy Guy. Quinn Sullivan, too, a 16-year-old prodigy he’s touring with and who opened the show on Saturday with an all-fireworks set of close to 10 songs. First apart, then together, the young disciple and the old master made for over two hours of pure showmanship.

I think it rubbed off on my son. He got a taste for playing live in public again. He has done a few gigs already, in a café with a band of classmates and their teacher: a bit of John Mayer, Herbie Hancock, a few originals. He’s outgrown the three-quarter-size Yamaha he had at 9; now he gets tutored in music at university. He’s 17.

I can’t remember everything Buddy Guy and young Quinn played at Metropolis, but I do remember my son’s enthusiasm at seeing and hearing them: the whistles and cheers he shouted out during the solos; the spring in his step as he ran down the stairs of the sold-out hall to film the 78-year-old Chicago’s bluesman when he made a surprise walkabout through the crowd; his amusement at the man’s profanity-laced replies to hecklers (the friendly kind who just can’t shut up); his bodyguard instinct to ask a pushy latecomer with a private supply of ice-cold beer cans hidden in his jacket pockets to please step aside so his dad could see the show.

No problem, no problem, everything’s cool – that’s the way it was, that’s how people react to him.

I stared at Buddy Guy’s two-tone shoes. “Is he wearing spats?” My boy smiled and I knew what he was thinking: Spats, the old gangster that George Raft played in Some Like It Hot. That was a perfect movie – our movie. Buddy Guy wasn’t perfect; he flubbed some riffs (“Shiiii-t!” ) but it didn’t really seem to matter. He played on.

His keyboardist tam-tam’d a Hammond organ sound, bobbing and weaving and swatting down whole blocks of notes with his paws. The rhythm guitarist with the cherry red snapback took centre stage and whacked out a solo. Sullivan’s drummer (the band’s producer) came back to shake a tambourine and sing duet on a couple of numbers.

All in the family, you know?

The man himself picked his guitar with his teeth, played it overhand, played it with a drumstick, covered Hendrix, switched to acoustic, sat on a stool, gave a tutorial on greats he’s known and mutually inspired: Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Eric Clapton. He has played Montreal 10 times in the last 20 years, once with B.B. King himself.

A boisterous duo of young francophone fans behind us kept screaming his name: “BODY GUYYY!” The man himself plugged his autobiography. There’s a moment in that book, When I Left Home: My Story (Da Capo Press, 2012), when the Louisiana-born guitar god nails what makes the blues the blues.

“Funny thing about the blues,” he says, “you play ’em cause you got ‘em, but when you play ’em, you lose ’em.”

I don’t know if my son, who’s so admirably even-tempered, ever gets the blues, let alone needs to lose ’em. I just know from the sound I hear that he has started to play ’em, thanks to a guy named Guy and a kid named Quinn. They showed that a musical education begins with listening. (Like my grandmother used to say: “Eat first, then talk.”)

Heckling the hecklers, the wise man said: “Shut the f--- up and you might learn something.”

On Saturday night, my son listened. Now I listen to him.

Watch the concert.

Paul Kelly, revisited

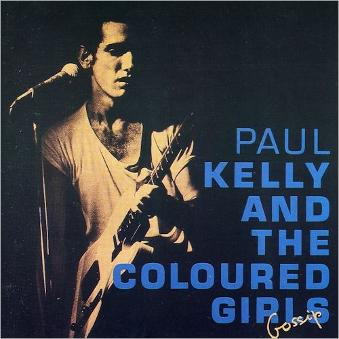

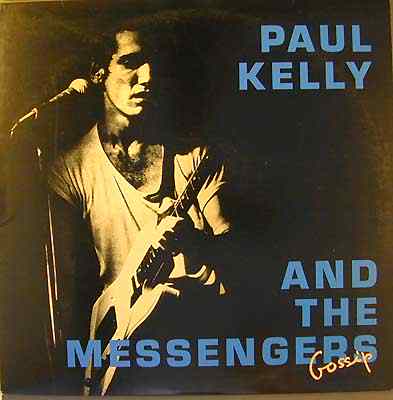

It all began with Gossip – at least it did for me. 1987 was the year I became what would turn out to be a lifelong Paul Kelly fan. It was the year I entered journalism school, and Kelly was my kind of songwriter. He wrote catchy songs that told simple, dark stories of love and loss. His lyrics were layered with literary allusions, his riffs rang with the twang of roots-rock and alt-country – part-Byrds, part-Dylan, part Townes Van Zandt. His accent was Australian, pretty nasal. And his sunken eyes had the haggard look of a dangerous man. That year in Ottawa, Gossip went 'round-and-'round my turntable so much the neighbours eventually complained. Turn it down? No way. I needed Paul Kelly like caffeine.

This was the pre-Internet age, and there was no Wikipedia or PaulKelly.com.au to tell me the LP was a kind of compromise. I was listening to the album's stripped-down North American version, 15 songs instead of 24, and a cover that identified Kelly's band as "The Messengers." As if. The band's real name was The Coloured Girls (lifted from the line in Lou Reed's "Walk on the Wild Side") but that was apparently judged too risqué for race-conscious America, so what we got on this side of the world was The Messengers. No matter – message received. Gossip became the soundtrack of my year at J-school: "Before Too Long," "Darling it Hurts," "Randwick Bells," "Adelaide." I was impressed that Kelly could even sing a line in French, and a historic one at that: Voici le temps des assassins!

Under the Sun followed in 1988, then came So Much Water So Close to Home (referencing Raymond Carver) in 1989. I dipped into the back catalogue, too, getting an import LP of Manila (1982), which was a disappointment (too raw for my taste), and a CD of Post (1985), which was a kind of demo for Gossip and much more listenable. A few years later, living in Paris, I went to the Australian embassy and, digging into the record collection in the library there, duped a tape of 11 live tracks Kelly recorded solo on stage in Melbourne and Perth in May, 1992; I still have it. I stayed a fan through several CDs released over the next decade – from Hidden Things and Wanted Man to Nothing But a Dream and Ways & Means, and his live acoustic A-Z Recordings. Eventually, though, I kind of lost the thread of the artist's narrative as he changed bands, did some acting gigs, wrote soundtracks, took on political causes (for Australia's aboriginals, notably), and wrote his memoir.

Recently, however, I was drawn back to my old fave through a documentary film called Paul Kelly: Stories of Me. Directed by Ian Darling, it fills in a lot of gaps in this enigmatic performer's life; I had no idea that heroin had been his on-again, off-again drug of choice for over two decades, nor that his grandfather had been an Italian opera singer, nor that Kelly is now revered by a whole new generation of young Australians as a kind of national bard. From the concert footage anyway, his audiences seem to know every line of every song he's ever recorded (there are more than 350).

With a library card, you can sign up for a free membership on Hoopla and watch the film. In the meantime, here's the trailer:

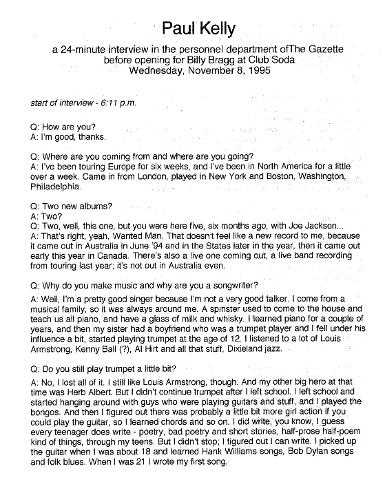

The documentary took me back to my own personal encounter with Kelly in late 1995, when he was passing through Montreal on tour with Billy Bragg. He'd been here six months before, opening for Joe Jackson at Théâtre St-Denis, and I'd gone to the show. Now we sat down with his publicist and I got out my list of questions – a fan's list more than a journalist's, really, full of close readings of his songs and questions about personal details of his life that I thought I'd gleaned from his lyrics. In the end, the interview was never published; The Gazette's entertainment editor at the time turned it down. But I did type it out, print it up and file it safely inside the sleeve of one of the albums I had at home – Gossip, as it turns out. Which kind of brings things full circle now. I'm too lazy to type it all up again, so here are scans of the transcript (errors included).

1

2

3

4

5

6

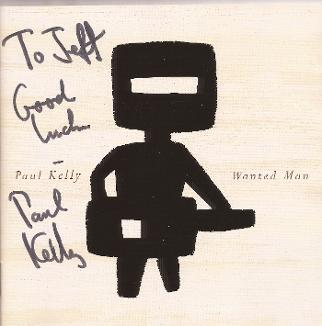

When our talk was over, I asked him to sign my CD of Wanted Man, and he did.

Cool cover, eh? Thanks for the memories, Paul Kelly.